Access the "Visual Guide to Wolf Dentition and Age Determination"

here.

How to use the guide:

The extensive guide is intended to be used as a reference for aging wolves. It also provides a basic understanding of dental terminology, anatomy, and some of the more prevalent conditions associated with wild canid dentition. The opening pages of the guide focus on providing the user familiarity with the dental formula, and the identification of specific teeth (e.g., nomenclature). The guide, containing many known-age skull specimens, clearly distinguishes notable and important characteristics between living and skull specimens for age determination. The hope is when field teams are handling wild canids, they may reference this guide to take more detailed notes allowing for a better picture of oral health.

Dentition terminology and anatomy: Terminology and anatomy is the foundation for the user of this guide. Even if, the identification of a specific condition or pathology cannot be adequately or definitively determined, the location may be appropriately described, documented, using anatomical and dental terminology described in the early pages.

Wolves have 42 teeth (between the cranium and mandible). Their dental formula is:

i 3/3 c 1/1 p 4/4 m 2/3

The dental formula represents one side of the mouth, so if you double the teeth listed in the formula, it will account for all 42 teeth. The first number 3/3 indicates the number of upper teeth present on one side of the cranium, whereas the second number 3/3 indicate the number of lower teeth on one side of the mandible. Wolves have four different classifications of teeth: incisors (i), canines (c), premolars (p) and molars (m). With this knowledge, the user will be able to identify specific teeth, reference their position within the mouth, and identify the unique faces of each tooth using the Dental Anatomy & Terminology pages.

Where do you start?

In addition to what is described in the guide, it is important to perform an initial oral health exam (this may vary in procedure and protocol based on your organization or agency). From this exam, a periodontal, calculus, plaque, and gingival index can be obtained to measure oral health in free ranging carnivores. However, this is something that should be discussed with your project veterinarian, and for the purposes of this guide, we do not cover these procedures at any depth. Critical components of an initial oral exam include the following (not listed in specific order):

1. Symmetry of the skull/head and associated muscle groups – any asymmetry or swelling; observe for draining tracts in and around the nose, eyes, mandible (they appear as pore like pustules that are secreting fluid, puss)

2. Mucous membranes – noting any oral or nasal discharge that appears abnormal

3. Lymph nodes – palpating the lymph nodes, documenting swelling and asymmetry

4. Heart & Lung auscultation

5. Hydration status – tent the skin

6. Visual presentation of the skin and fur – assess for any abnormalities

7. Eyes & Ears – observe for any discharge or abnormalities

After completing your initial assessment, the user should reference the guide for the following:

1. Are all teeth present? Are there extra teeth or too few teeth?

2. Is there normal interdigitation? Can the animal close and open its mouth normally? Are there any occlusions in the mouth? (e.g., misaligned teeth, overbite, underbite)

3. Are there any missing teeth, fractures, or breaks? Are there tooth remnants?

4. Any discoloration, staining?

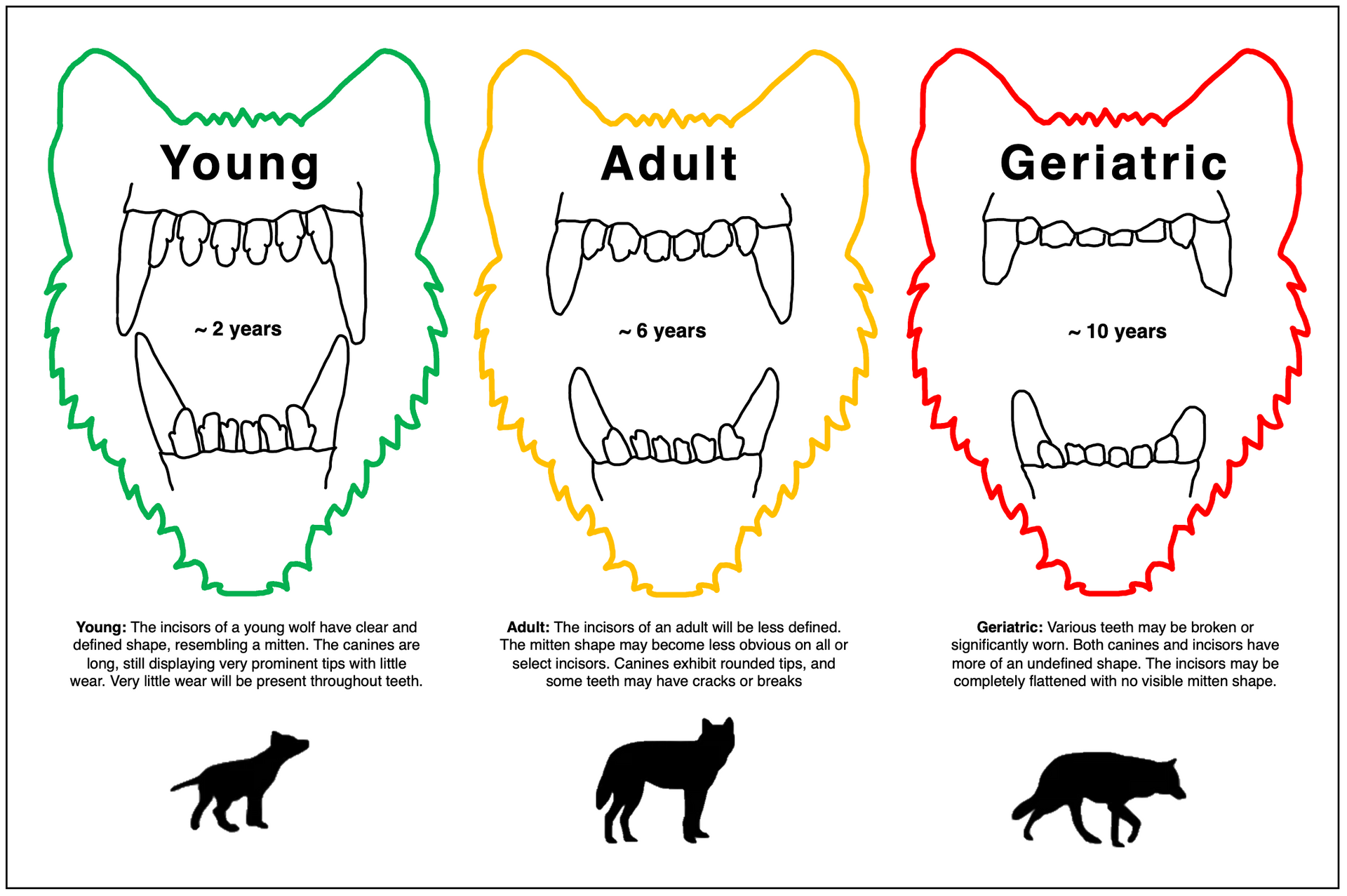

5. What does the wear pattern look like? Users may reference some of the descriptions provided in the age classification section of the guide

6. Is there any dentin or pulp exposure?

7. Is the gum tissue inflamed, swollen, or bleeding around any teeth?

8. Any indicators of previous exposure to disease? (e.g., enamel hypoplasia, hypomineralization)

9. Any indications of ulcers? Oral trauma? (e.g., broken or disformed mandible, alveolus)

If the user has any doubt for these questions, examples are located within the guide. Photos are always highly recommended during wildlife handling, especially of the teeth. Detailed photos may allow for further assessment post capture and minimize the amount of time the animal is under anesthesia.

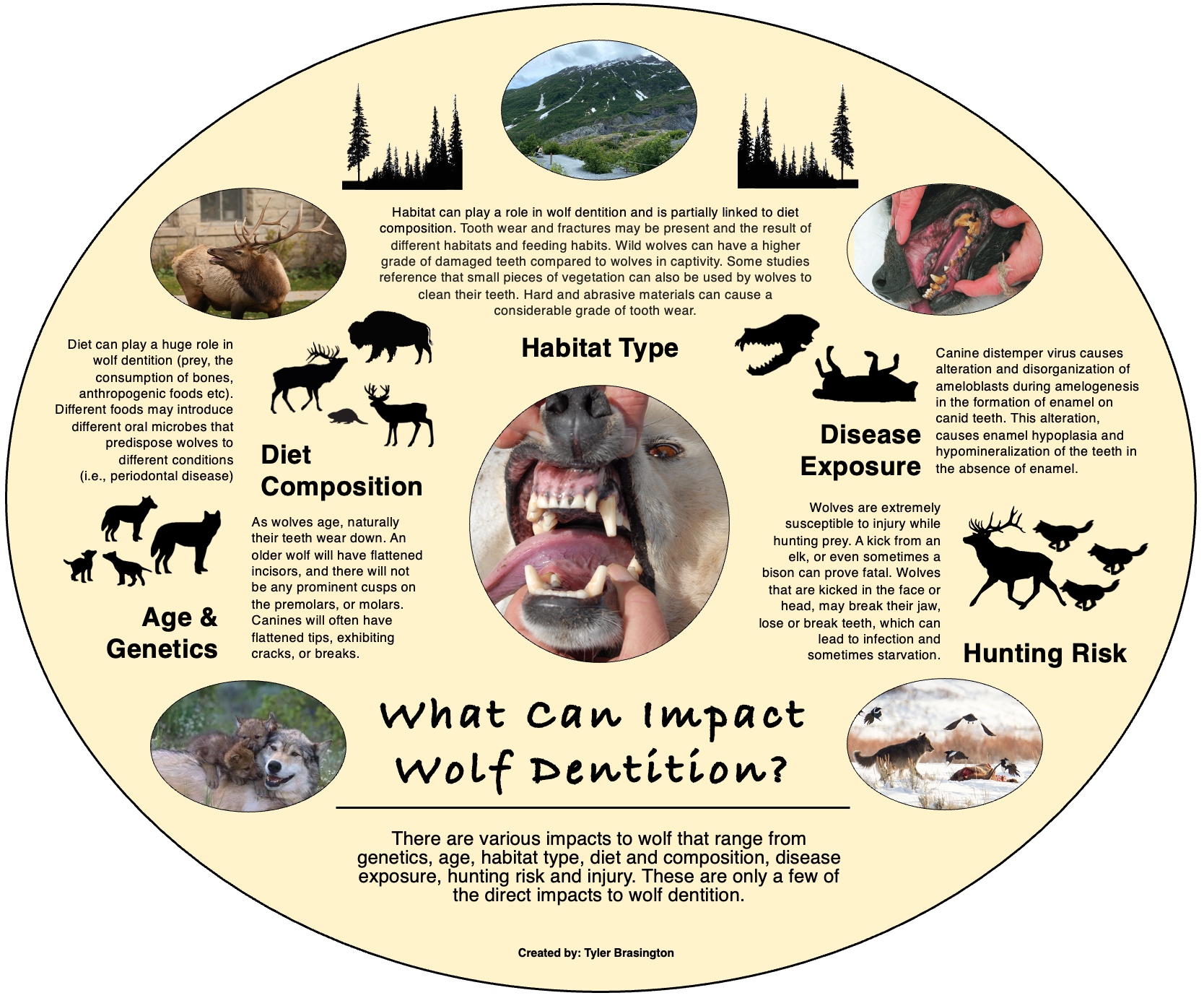

What impacts wolf dentition?

There are various factors that may impact wolf teeth and oral health. Notably, disease such as canine distemper virus (CDV) can cause malformed, pitted teeth and enamel hypoplasia. Other factors include habitat, diet composition, age and genetics, and damage from hunting events. While this is not an exhaustive list, these are the predominant factors which impact wolf dentition.

Enamel hypoplasia:

Enamel hypoplasia and associated defects result from severe general disease at young age (most often canine distemper virus) or local trauma to a deciduous tooth causing infectious pulpits. As a result, the underlying mature teeth will exhibit enamel defects (Janssens et al., 2016). Döring et al., 2018 macroscopically examined 392 grey wolf skulls and found enamel hypoplasia in five skulls. Canine distemper virus causes alteration, and disorganization of ameloblasts during amelogenesis in the formation of enamel on canid teeth. This results in enamel hypoplasia and hypomineralization of the teeth in the absence of enamel. Enamel hypoplasia generally presents with discolored, pitted, malformed, and missing teeth. There is a section within the guide that users may reference for the presentation of enamel hypoplasia and hypomineralization.

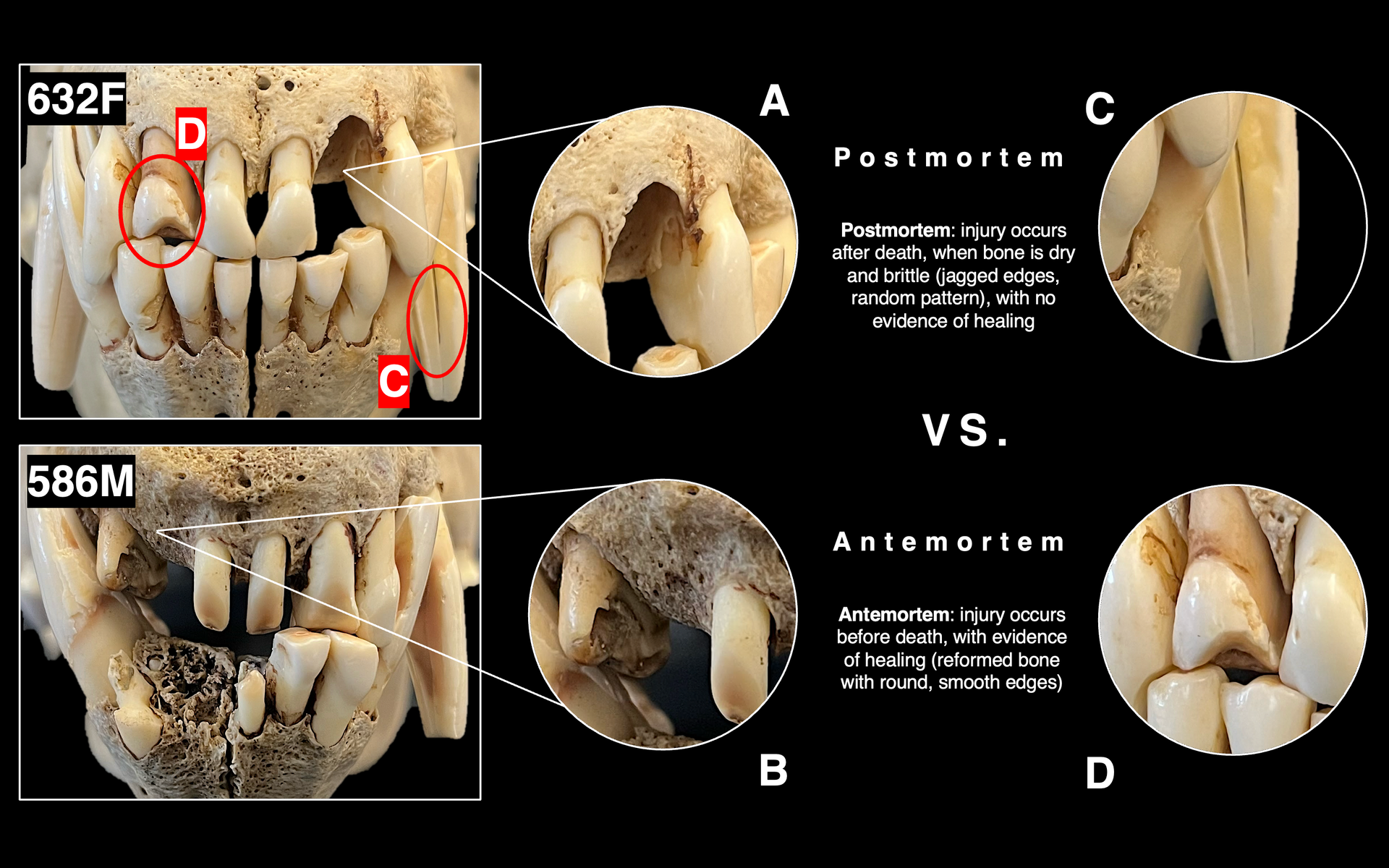

Differences between ante, peri, and postmortem dentition: This guide utilizes known-age skull specimens, so we can provide the user with information on how to distinguish between ante, peri, and postmortem dental injuries.

These distinctions are important for the user to understand, especially for those wolves in older ages classes who frequently have damaged, cracked, or missing teeth. Distinguishing whether the specimen incurred the injuries during life, or whether it was during handling/processing of the skull specimen – will help the user better understand patterns.

Literature Cited

Döring, S., B. Arzi, J. N. Winer, P. H. Kass, and F. J. M. Verstraete. 2018. Dental and temporomandibular joint pathology of the grey wolf (Canis lupus). Journal of comparative pathology. 160: 56-70.

Janssens, L., L. Verhaert, D. Berkowic, and D. Adriaens. 2016. A standardized framework for examination of oral lesions in wolf skulls (Carnivora: Canidae: Canis lupus). Journal of Mammalogy. 97:1111-1124.